- Home

- Susan Jaques

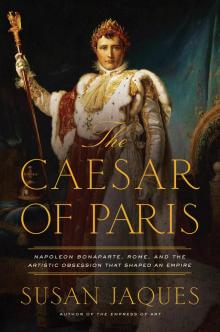

The Caesar of Paris Page 8

The Caesar of Paris Read online

Page 8

When twenty-two-year-old Charles Percier arrived at the Palazzo Mancini in 1786, he felt overwhelmed. “I went from antiquity to the Middle Ages, from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, without being able to settle down anywhere,” Percier confided to a colleague. “I was divided between Vitruvius and Vignola, between the Pantheon and the Farnese Palace, wishing to see everything, learn everything, devouring everything and being unable to resolve to study anything.”7

Over the next five years, Percier produced an astonishing two thousand drawings. This did not include his official assignment—a study of the iconic one-hundred-foot-tall Trajan’s Column in the Roman Forum. To get close enough to measure and sketch the towering marble bas-reliefs, Percier spent four months being hoisted up and down in a basket with a scaffold and pulley system. “. . . the cursed column eats all of my time . . .” he complained to his friend Claude-Louis Bernier in April 1789. While Percier was immersed with the column, his friend Pierre Fontaine was studying and sketching ancient Roman aqueducts.

Completely captivated by Rome’s ancient ruins and monuments, Percier explored excavation sites, private collections, and museums. In the Capitoline Museum, he sketched sarcophagi and an urn decorated with musical putti. Together, Percier and Fontaine studied Rome’s monumental Egyptian obelisks and the Pyramid of Cestius, along with objects from the nearby Etruscan towns of Viterbo and Velletri, prompting their fellow students to nickname them “The Etruscans.” The duo was also known as the sobriquets Castor and Pollux, the inseparable mythological twins.8

On his way back to Paris, Percier trekked across northern Italy, stopping in Ancona and Ravenna, then northwest to Parma, Cremona, Mantua, Venice, Bologna, and Ferrara. Throughout his journey, the prolific draftsman continued to sketch ruins, monuments, and buildings from different periods. “Venice completely disoriented me,” Percier wrote British sculptor John Flaxman. “It struck me as one of the most beautiful cities in Italy . . . the marble, the water, the paintings, everything ravished me. However, in summer the small canals smell bad. That’s the other side of the coin.”9

Percier and Fontaine returned to Paris just in time for the French Revolution. Percier assembled his drawings from Italy in a series of volumes, keeping eight with his most beautiful sketches in his studio as a reference.10 In Italy, Percier developed an appreciation for combining architecture and decoration. Writes Tom Stammers, “Italy taught Percier to think of fixed structures and their flexible contents as a single entity.”11

Living together in cramped quarters on the third floor of a building off rue Montmartre, Percier and Fontaine eked out a living designing exotic theater sets for the Paris Opéra. In 1798, they published the first of their two books based on their Rome sojourn—Palais, maisons, et autres édifices modernes, dessinés à Rome. During the Directory regime when luxury consumption made a comeback, the duo began renovating interiors for businessmen who had acquired residences of the nobility.

Of all their clients, France’s frugal, temperamental first consul and his glamorous, spendthrift wife would prove the most challenging and rewarding. Napoleon, who had grown up in comfortable but modest circumstances on the island of Corsica, often became irate over the renovation bills for Malmaison. To avoid a scene, Joséphine offered to pay an upholsterer an extra ten thousand francs to keep her bedroom’s decorative tassels, braid, and fringe simple.12

Further complicating matters, the consular couple often disagreed, as was the case with Joséphine’s passion for tents. Upon seeing Percier and Fontaine’s striped sentry tent at the entrance of Malmaison, Napoleon demanded to know who authorized the structure and told Fontaine that it looked like “a booth for animals on display at the fair.”13

Working within the constraints of the old château, Percier and Fontaine began with the entrance hall. They created a Roman atrium with four scagliola or faux-marble columns, a ceiling painted to imitate granite, and pale yellow walls adorned with antique trophies. The designers enhanced the Roman ambience with white marble busts and two bronze busts of philosophers. The atrium’s quietude was interrupted after Joséphine, perhaps nostalgic for Martinique, installed aviaries with noisy tropical birds.

The addition of sliding mirrors in the central arcades opened the entrance hall onto the billiard and dining rooms. After extending the dining room with a semicircular section, Percier and Fontaine covered the floor with dramatic black and white marble squares (along with the billiard room and adjoining spaces). Inspired by the Villa of Cicero in Pompeii, Percier designed a series of graceful female dancers for the dining room. Artist Louis Lafitte translated his drawings into a series of decorative wall paintings.

As Napoleon increasingly spent long weekends at the château, it began to double as a country home and seat of government. Over ten dizzying days in July, Percier and Fontaine built a meeting room on the ground floor of the south wing. Shaped like a military tent, the Council Room was covered in blue and white striped cotton trimmed with red and yellow wool fringe. Ancient helmets and swords adorned the doors, capped with eagles, the Roman symbol of victory. Between January 1801 and September 1802, the room hosted some 169 councils. The Concordat and 1803 sale of the Louisiana Territory to the United States were decided here.

Next door, Percier and Fontaine combined three small rooms in the south corner to create a library for Napoleon. Fontaine removed the partition walls and commissioned the Jacob brothers to fashion the teak woodwork. Mahogany paneling, desk, and bookcases held some 4,500 volumes, selected by Fontaine, many bearing the monogram “B-P” for Bona-Parte. Frederic Moench’s decoration of the vaulted ceiling after Percier’s designs featured Minerva leaning on her spear and Apollo with his lyre. Surrounding Minerva and Apollo were portrait medallions of great authors—Homer with his owl, Virgil with a wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, Dante with the lion of Florence, and Voltaire with the Gallic rooster (probably by Lafitte). According to Alain Pougetoux, Moench did not intend to produce frescoes, but he didn’t have time to let the plaster dry. Napoleon ordered the library done quickly.14

A hidden staircase behind the mirrors led to Napoleon’s two-room apartment upstairs. By mid-September, 1800, Fontaine wrote: “Everything is now in place, and even though the First Consul found that the room looked like a church sacristy, he was nevertheless forced to admit that it would have been difficult to do better in such an unsuitable space.”15

To realize their heroic new decorative style in chairs, cabinets, and tables, Percier and Fontaine began a collaboration with the Jacob brothers, Paris’s foremost ébeniste or cabinetmaker. After furnishing many of the royal palaces for Marie Antoinette, Georges Jacob had been saved from the guillotine by his friend Jacques-Louis David. In 1796, he retired, turning over the family business to his sons Georges Jacob II and François-Honoré-Georges Jacob. When his older brother’s death in 1803, François-Honoré expanded the firm under the name Jacob-Desmalter & Cie, employing over 330 workers in some sixteen workshops. Among its remarkable furnishings for Malmaison was a bureau for Joséphine, designed with a Roman arch and a golden frieze with four winged figures of Victory.16

Ancient Rome also inspired Percier’s designs in gilt-bronze. Among the ornamental objects for Malmaison, noted Parisian bronzeur and gilder Pierre-Philippe Thomire created a candelabrum and vase for Napoleon’s bedroom with a winged Victory holding a laurel wreath overhead supporting a branched candlestick. Trained initially as a sculptor under Augustin Pajou and Houdon, Thomire switched to his family’s bronzesmithing business. After an apprenticeship to Pierre Gouthière, he formed his own atelier in 1776 and worked for the Crown toward the end of Louis XVI’s reign. In 1783, Thomire became exclusive supplier of gilt-bronze mounts for the Sèvres porcelain factory. He managed to survive the Revolution by making arms and ammunition. Under the Consulate, Thomire returned to decorative bronze work, employing hundreds in his thriving workshop. Thomire supplied finely chased and gilded mounts for furniture and clocks to the leading ébénistes.

Combining motifs and martial imagery from ancient Rome, Etruria, and Egypt, Percier and Fontaine created a singular style for Malmaison. Joséphine heightened the effect by presenting her collection of antiquities as decorative objects. During the Consulate and the Empire, Malmaison “took on the aura of a Roman domus,” write Martine Denoyelle and Sophie Deschamps-Lequime.17

But Pierre Fontaine soon clashed with Joséphine over Malmaison’s park. The opinionated architect preferred classical French gardens; his patron loved the natural English landscapes. “She wants us to work on the gardens, the waters, the conservatories,” wrote Fontaine in 1800, describing her demands as “without measure and without limits.”18 Joséphine’s Anglophile gardener Jean-Marie Morel opposed Percier and Fontaine’s bold designs. After submitting their resignation, Fontaine expressed relief, noting that Joséphine’s “desires are orders that one cannot refuse, and whose outcome even the subtlest would be unable to foresee.”19

The disagreement hurt the designers’ relationship with Joséphine, but not her husband. In 1801, Napoleon appointed Percier and Fontaine co-architects to the government.

After Napoleon’s November coup d’état, he and Joséphine left their modest residence on rue de la Victoire for the Petit Luxembourg. Located just west of the sumptuous Palais du Luxembourg built by Marie de’ Medici, Petit Luxembourg’s recent tenants included the future Louis XVIII and his wife (before they fled revolutionary Paris in 1791) and four of the five members of the deposed Directory.

Just three months later, Napoleon and Joséphine moved again. On the afternoon of February 19, 1800, a procession of carriages left the Luxembourg accompanied by a military band. The three consuls rode in a coach driven by six white horses—a gift from Habsburg Emperor Francis II after the Treaty of Campo Formio. Some three thousand soldiers lined the streets and crowds cheered as the cortege made its way to the Tuileries Palace, west of the Louvre.

From the balcony, Joséphine watched with her daughter Hortense and sister-in-law Caroline Murat as her husband mounted a horse and conducted a military review in the courtyard below. Recognizing the impressive effect of his soldiers in their elegant uniforms, Napoleon would restage this spectacle twice a month, to a fanfare of drums and trumpets.

Soon after his review, Napoleon learned that George Washington had died at Mount Vernon. He ordered a wreath for the tomb of the American hero. During an official period of mourning, black crepe draped the Republic’s flags and pennants. “This great man fought to overthrow tyranny,” read the official pronouncement. “. . . His memory will ever be dear to the French People, as to every free man in both hemispheres, and especially to French soldiers who, like him and the other soldiers of America, are fighting for equality and liberty.”20

During France’s own recent revolution, the Tuileries Palace was repurposed as a royal prison. After being driven out of Versailles in 1789, Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette were held under house arrest at the Tuileries before being tried and beheaded. Napoleon had witnessed the occupation of the palace in June 1792 when it was ransacked and looted by a revolutionary mob. Its staircases were still stained with the blood of Swiss Guards who had tried to protect the royal family.

Tuileries had long been associated with royal extravagance. In 1564, recently widowed Catherine de’ Medici began building a new palace perpendicular to the Seine. The property overlooked gardens and marshes that were later named the Elysian Fields after the heaven of the heroes of Greek mythology. The palace and garden were named Tuileries after the local tile factories or tuileries. But the superstitious queen put the kibosh on the project when her astrologer predicted she would soon die “near Saint Germain.” The Church of Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois was too close for comfort.

Catherine’s son-in-law Henri IV finished the palace, constructing the Grand Gallery to connect it to the Louvre. Louis XIV would spend his last night in Paris at the Tuileries before moving permanently to Versailles. In 1715, his five-year-old great grandson and heir, the future Louis XV, moved to the Tuileries from Versailles. Under his rule, the promenade through the Tuileries Garden became a long, broad avenue known as the Champs-Élysées.

Now Napoleon gave architect Étienne-Chérubin Leconte one month to refit the palace. During the Directory, the palace was occupied and subdivided by the Convention and its committees. One of the first changes was to remove the red republican caps and other revolutionary symbols painted on the walls. “Get rid of all these things,” Napoleon told his architect. “I don’t like to see such rubbish.”21

On the first floor at the south end of the palace, the Gallery of Diane was replaced by a Gallery of Consuls. Lucien Bonaparte, now Interior Minister, ordered nineteen ancient and contemporary marble portrait busts from nineteen different sculptors including Augustin Pajou, Claude Dejoux, Jean-Joseph Espercieux, and Pierre Cartellier.22 Lining the gallery walls were busts of Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Brutus, Demosthenes, Scipio, Hannibal, Cicero, and Cato. The military pantheon included a number of France’s enemies like Frederick the Great, Eugene of Savoy, Gustavus Adolphus, and the First Duke of Marlborough, who served briefly under France’s General Turenne against the Dutch. “Brave men impress me, regardless of which land they represent,” Napoleon later inscribed in a biography of the Duke of Marlborough.23

The first consul’s relatively small entourage consisted of aides-de-camp, secretaries, and servants. Géraud-Christophe-Michel Duroc, governor of the palace, oversaw security and general operations. Napoleon’s future brother-in-law, Joachim Murat, was named commander of the ten-thousand-man consular guard. Anne-Jean-Marie-René Savary, who had served under General Desaix in Egypt, was entrusted with palace surveillance, commanding the seven hundred member legion of gendarmerie.

Napoleon soon replaced architect Leconte with his favorite designers, Percier and Fontaine. On October 4, 1801, Fontaine wrote: “The First Consul is very much occupied with the decoration of the apartments of the Tuileries. He wants Versailles to be all that can be found in the museums and warehouses, that the great pictures of the battles of Alexander by Lebrun be placed in the gallery of Diana. . . . We visited every detail in detail when, in one of the saloons of the great apartment, he found several members of the Tribunate. ‘You see,’ he said, ‘trying to do honor to the country which I am governing, and now that we have peace, we are going to occupy ourselves with the arts.’”24

To realize his designs for the Tuileries Palace, Charles Percier turned again to cabinetmaker François-Honoré-Georges Jacob-Desmalter, along with Alexandre Brongniart, director of Sèvres, and silversmith Martin-Guillaume Biennais. In 1798, Biennais allowed Napoleon to make purchases at his Paris shop on credit. As first consul, Napoleon returned the favor, appointing Biennais as his official goldsmith.

For Napoleon’s bedroom, Biennais produced an elegant yew, gilt bronze, and silver washstand known as an athénienne after a design by Percier (the ewer and lavabo were made by Marie-Joseph-Gabriel Genu). Its form came from the Greco-Roman three-legged perfume burner or brazier also used for offerings to the gods. The antique brazier was generally made of bronze, but could also be done in copper, silver, stone, or gold. With classical art in vogue, the antique tripod enjoyed a comeback.

Biennais decorated Napoleon’s luxe athénienne with gilt bronze antique motifs of swans, dolphins, chimaeras, bees, and eagles. According to Wolfram Koeppe, dolphins and swans carried an especially powerful message—Napoleon’s place as rightful heir to Louis XIV. The firstborn son of the French king was called the Dauphin or dolphin. Louis XIV, the Sun King, linked himself to Apollo, who himself was associated with swans. Dolphins and the winged sea creatures on the frieze around the shelf also evoked Napoleon’s birthplace, the island of Corsica.25 For his business card, Biennais chose a tripod crowned by a swan with spread wings.26

Gradually, the rooms of the Tuileries Palace were decorated and furnished. The second floor of the west wing housed Napoleon’s private apartments and the state apartments with the state c

abinet where the Administrative Council and Cabinet met. Joséphine and her son and daughter occupied Marie Antoinette’s rooms on the entresol, or ground floor. Despite the refurbishing, Napoleon and Joséphine never enjoyed the Tuileries, where it was impossible to walk without being seen by the public. Joséphine especially enjoyed the privacy of Malmaison where she was surrounded by her gardens. The Tuileries remained Napoleon’s official residence, soon the seat of his imperial court.

With Malmaison too modest for the head of the French Republic, Napoleon took possession of the former royal Château de Saint-Cloud for his main summer residence. During his coup d’état, Napoleon had seized power in Saint-Cloud’s Orangery. Located near the Seine some three miles west of Paris, the château had been enlarged in the seventeenth century by Louis XIV’s brother Philippe, Duke of Orléans (who died there), and again by Marie Antoinette after Louis XVI acquired the palace for her in 1785. In September 1801, Percier and Fontaine began renovations.

About the six-story palace, Fontaine wrote: “The First Consul fixed, but in a somewhat vague manner, the distribution of the apartments. . . . We do not know what to do with the chapel.”27 Like at the Tuileries, some of Saint-Cloud’s furnishings came from the Garde-Meuble Impérial and palaces of the Republic. Much of the furniture for Joséphine’s apartments was new. Located in the left wing, her suite included a dining room, music room, two salons, bathroom, boudoir, and bedchamber.

Overlooking the forecourt, the boudoir featured four large mirrors and a fireplace. Percier decorated the room in red, white, and gold, adding white taffeta curtains and cerise drapes. There were two large porcelain Sèvres Medici vases, goblets made of “oriental agate,” and a Lepaute clock supported by two chimeras. Percier also designed an elegant gondola chair incorporating one of Joséphine’s favorite motifs, the swan. Made of gilded beechwood and upholstered in cerise silk velvet, the innovative seat was inspired by the ancient klismos chair and featured deep convex backs and swan-shaped armrests painted white.28 The swan had appeared in various forms during antiquity, often in connection with the myth of Leda, Apollo, or Venus.29

The Caesar of Paris

The Caesar of Paris